There are a few places in the world that just by name, conjure evocative reactions. Often these are areas where, unfortunately, tragedy has struck - places where events unravelled that have sent tremor waves of shock felt across the globe.

One such location has been a fascination of mine for a long time. And that place is Chernobyl.

Photographing decaying and derelict buildings has long been an obsession of mine, something I've written and blathered on about many times. I yearn for it. I crave the ability to traipse through stale, dank crooked structures; rotten walls, peeling paint. Their ghostly existence crying out to be photographed - the documentation of manmade decline as nature engulfs it.

Photography lends itself so well to capture these haunting scenes, the emptiness, the decay - which never stops, never pauses - only within the four walls of the photograph.

Visiting Chernobyl had become a dream of mine. I had dreamed of seeing Pripyat, the city near the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, where nearly 50,000 people had lived between 1970 and 1986. On April 27th 1986, the day after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the city was evacuated, what is left is a ghost town. Buildings not used in thirty years; roads not been driven on, the swimming pool not swum in, the kindergarten cots not slept in.

This July, I was lucky enough to finally visit Chernobyl. The two day tour was probably one of the most incredible experiences of my life. I have explored many derelict buildings over the years, but apart from Imber, the small English village taken over by the military during WWII, I had never before had the chance to visit an entire ghost town - a cornucopia of abandoned treasures.

Trips to Chernobyl, have been allowed since the area has been deemed more safe, but there are still many precautions one must take when visiting (and quite rightly so). We had been given advice on what clothes to wear, and told to not touch things, or step on certain things. Moss for example, is particularly good at absorbing radiation so is likely to emit high levels of radiation so you are warned to not walk on it. You can imagine how difficult it becomes trying to avoid doing so whilst exploring Pripyat, trying to take in everything around you.

It is also strictly forbidden to remove anything from the exclusion zone. Entry into Chernobyl requires passport control, and the area is heavily guarded. You are not allowed to eat or drink whilst walking around Pripyat - and you can only do so whilst on the bus which would transport us around parts of the city which we could not travel by foot. During our stay in the Chernobyl hotel, there is a curfew by evening and no one is allowed outside after 8pm. You are screened regularly, having to stand in these bizarre 1970s sci-fi film-esque machines, that check you for any radioactive contamination.

When faced with these rules and regulations, the reality of where you are visiting very much strikes you. This is not a game, not a jolly. This is something that must be treated with respect, as you risked putting yourself in grave danger otherwise.

The trip began as we were taken to a kindergarten. The walls were seeping with branches and foliage and peeling crusty paint. What was left was a tragic reminder of the young lives who frequented there - dusty broken shoes, toys, torn books. So many items that looked like they had just been dumped. Rotting dolls like something out of a Stephen King film, and rows of skeletal wire cots that resembled an odd communal prison cell.

The personal items strewn across the decaying floorboards conjure so many questions - who wore this small shoe? Who did they grow up to be? Did they survive? Who clutched the teddy bear and dropped it that day in 1986, not realising they would never get to return to fetch it?

We were taken to many buildings and various areas in Pripyat. The culture palace, with a theatre and its stunning broken backstage.

It was a myriad of lighting rigs and grids of wires, now spookily silent, patiently waiting for the next performance that will never come.

The culture palace as it is today from the outside:

As the same culture palace as it was originally:

We saw one of the vast empty swimming pools, looking gaunt and hungry without its water; bright light streaming down onto white tiles through the huge windows - bizarrely striking against the dirt and graffiti that was building up. The suicidal looking diving platform still proudly erect, angular and defiant.

We explored a school. Pripyat had around 20 schools for the 5,000 children who lived there.

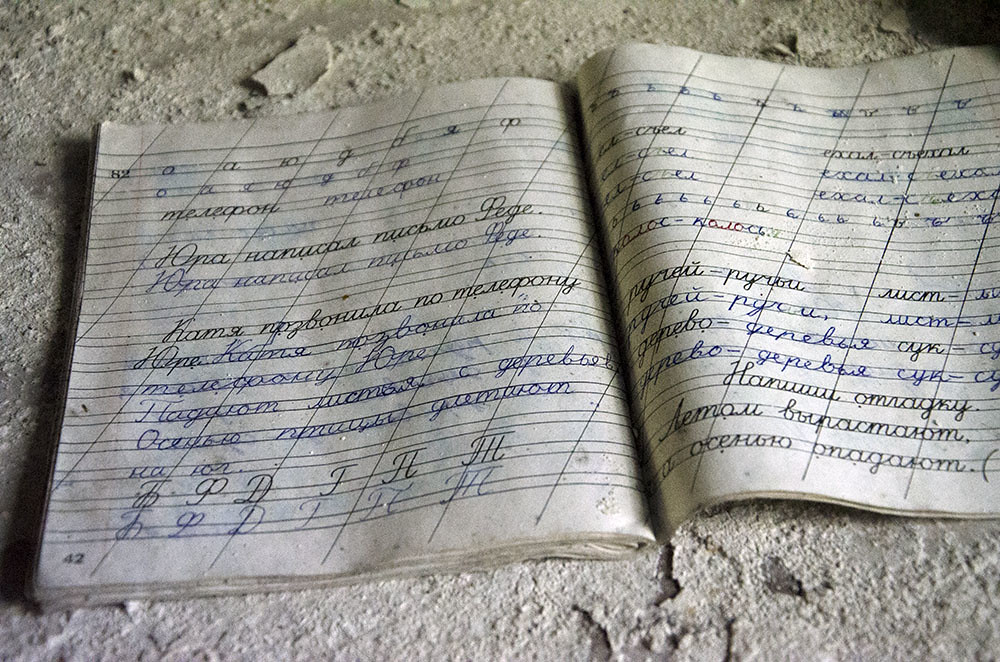

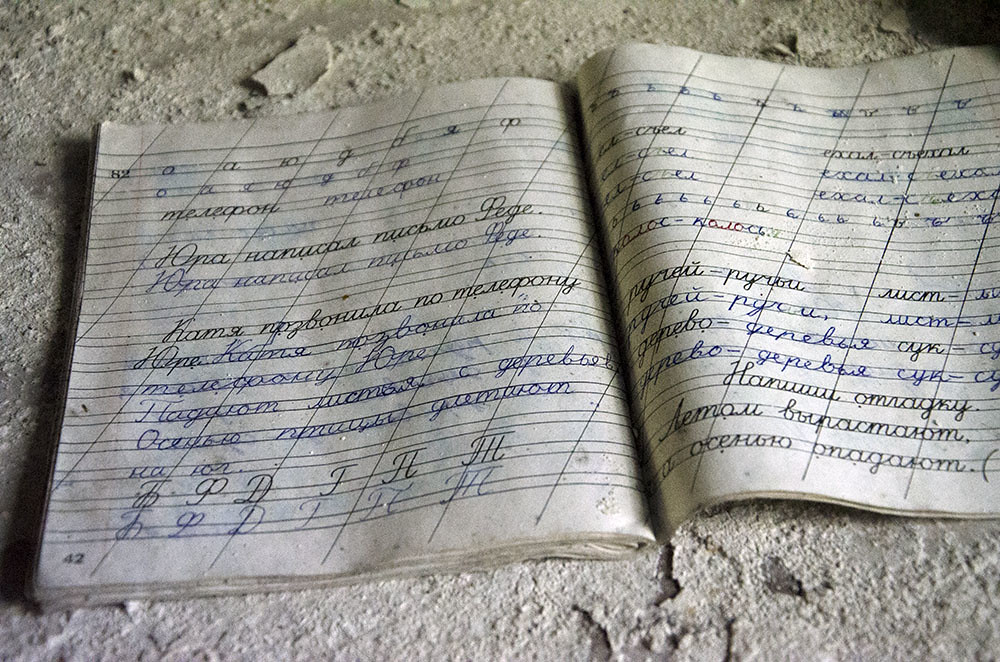

The school we visited was a zombified grange hill. So much of the ghostly remains resembled memories from my own school days: the corridors, the small chairs, books, science labs - yet these were all decomposing and decaying - vast broken rooms filled with empty dying desks, crumpled text books, written work books in perfectly scripted Russian/Ukrainian which was still legible. The poignancy was striking - when a child had worked so hard and taken so much care on this work I was stood near, little did they know it would one day be dirt ridden and lying upon a decaying floor, as part of a strange time capsule fodder for photographers.

Communist propaganda posters still hanging from the walls - Lenin, workers, anti-west diatribe. Cold war teachings. Something that seemed to only exist in history books I had seen in my own school - here they were for real.

It was in the school which I saw one of the most incredible sights I have ever witnessed - a sea of decaying gas masks. Gas masks themselves always look so alien and menacing. This surreal scene was an infinity ocean of cold war atomic nightmares. It churned your stomach, it made you gulp. The black holes for eyes, they resembled deformed leathery skulls. Gas masks, war. The threat. It was, of course, a reality for daily lives for the people of chernobyl.

One of the most impressive structures in Chernobyl that we visited was the 'woodpecker' - an incredible mammoth duga radar structure. It derived its nickname due to the sound it broadcasted - sharp, repetitive tapping noises, very much like a woodpecker.

There were many conspiracy theories over to what the radar tower's purpose was - with many insinuations and allegations of spying, and even mind control. Of course, none of these were ever proven. Now, the structure still stands proud....just eerily silent. Standing near it, you marvelled at its sheer size and formed beauty. Climbing the tower, scrambling up wobbling ladders you got the overwhelming sense of how minuscule you were. You were just an insignificant entity. The machine was the dominate power.

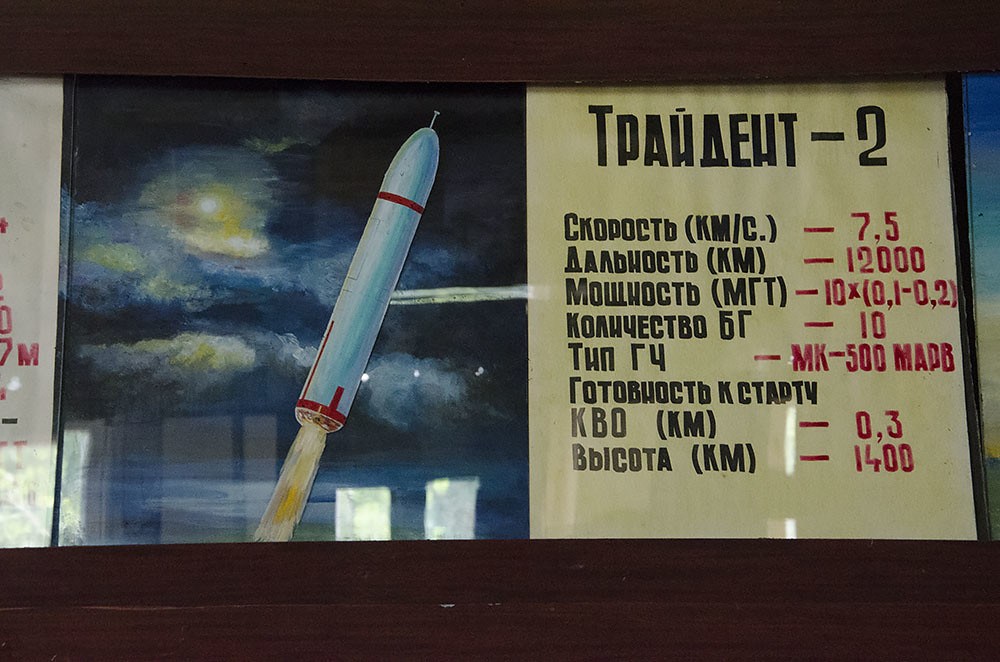

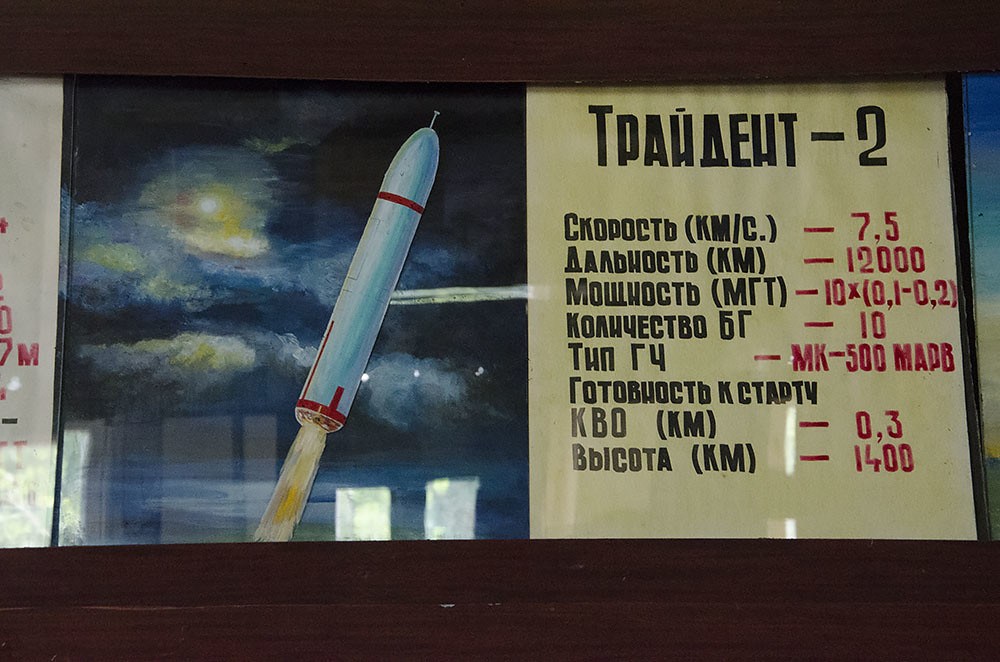

Inside the duga buildings, a control room contained warnings of attack, yet with oddly crude posters which almost resembled school drawings of nuclear rockets. It had a beautiful naivety, yet the science it was representing, was very much contradicting this.

One of the most famous areas of Pripyat was the fairground. It was meant to be opened on the May day celebrations - the disaster, of course, scupper these plans. The fairground that never was. The huge abandoned ferris wheel has become one of the icons of Chernobyl. Walking up to the area, the ferris wheel suddenly poked through the trees, its yellow carts so recognisable looming on the horizon. It made my skin prickle and the hairs on my arms stand up.

The fairground had languishing dogem cars, rusting away waiting to be driven; empty swing boats waiting to swing. Still. Expectant but dead. No sounds of children happily playing. Just static rusty structures waiting to die.

(For a peak at what the fairground looked like shortly before the evacuation - here is an interesting photograph of the ferris wheel)

We climbed 14 floors of stairs to the roof of a defunct crumbling residential building, and saw the incredible view across Pripyat. You could see for miles into the horizon. One side there was nothing but trees, the other side, the nuclear reactor stuck out into the landscape like a curved silver beast, glinting in the glorious sun shine. The reactor looked so close. The reactor *was* so close. You could imagine how quickly the radiation would have spread to the city....

And yet at times, as I gazed into the horizon on the gloriously sunny day, it felt so peaceful. So quiet. It was almost tranquil. Such a contrast to the thought of what had happened there.

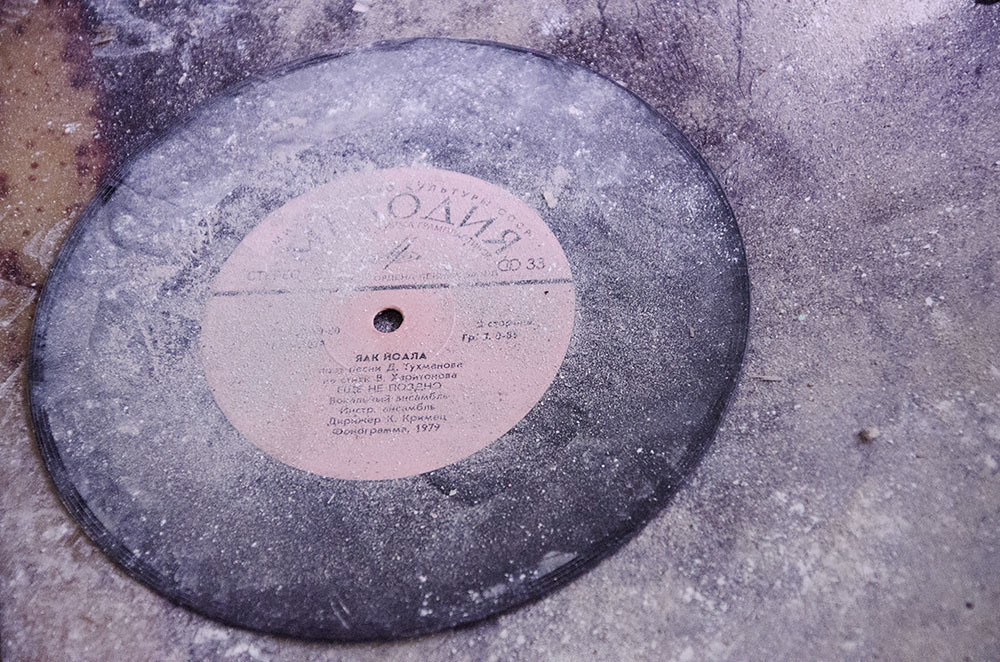

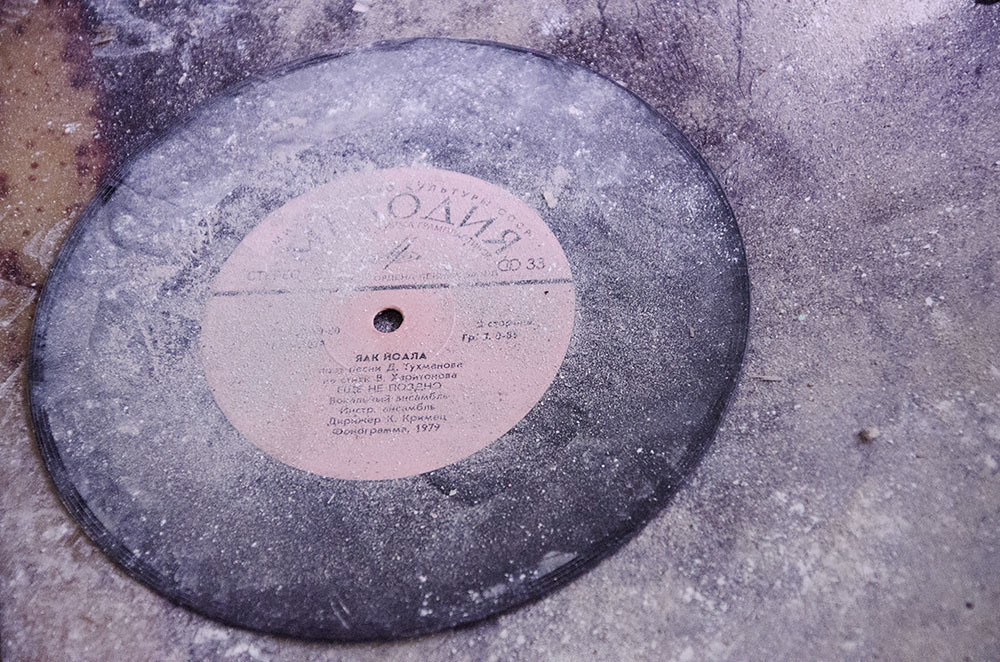

We were taken to a shop, a factory, cafeteria, the hospital and the cinema. All places of such mundane daily routine, of pastimes, of work, or places of social interaction - now dying and deteriorating; signs hanging off, rubble strewn, windows broken, ovens caked with rust not baked goods. Vending machines. Beds. Random items abandoned - a pepsi bottle, a hard hat, pill bottles, an old vinyl record, a torn sofa. Objects of life, signs of life, yet there is no life.

The beauty of these broken items sometimes took my breath away. The huge cooling tower. The light against the beautiful broken glassed windows of the cafeteria, crystalloid patterns that could be in another life, hanging in an art gallery. The creepy children's camp - set in the forest and evocative of as many woods horror films you can imagine. The stunning and oddly satisfying athestic of peeling paint - the crusty curls clawing out of the walls as if their bony fingers were coming alive. The dark rusty signs or faded red propaganda posters; beautiful in their colour and form. The emptiness of an abandoned room, now useless in its initial purpose, dripping with this tragic well of loneliness.

It was all quite overwhelming. And sometimes macabre.

Nothing was more a deadly wake up call of the dangers in chernobyl, than the sight and sound of the Geiger counter alarm, approaching one of the most radioactive items still left in Pripyat - the claw. The Geiger counter was brought out at various times during our trip. Sometimes it was unnerving (but also sobering and important) to how suddenly you would be near an item that was setting the alarm off on the counter. Radiation - the silent and invisible assassin. There is something more frighting about a deadly threat that you cannot see, cannot smell, cannot hear.

'The claw', however, was off the scale. You are not allowed close to 'the claw' - a terrifyingly industrial metal claw that was used to clean up nuclear waste after the disaster. Our guide placed the Geiger counter near, and we watched in awe as the alarm spiralled into high pitched cacophony. This was real. This was dangerous.

We slowly crept away.

One morning of the tour, we visited the house of a chernobyl resident. An odd experience, one that I was not sure I was comfortable with. She welcomed visitors regularly, showing people around her home and land.

Money was no use to her, instead, we brought her items such as sugar and salt. She spoke to us via an interpreter, explaining that she had worked in the reactor, and had been evacuated the day after the disaster, but had returned to live a year later and had lived there ever since.

She grew many crops, and these were all tested safe for consumption. Her house was primitive, her life was basic. She lived alone with her dog and cats. Whilst she made us feel very welcome (she gave us her own homemade moonshine and bread), I felt intruding, I felt as if I was patronising her by just being there.

It was a reality check to how some people live in the world, something I am far too often blinkered to - her oven was a hole in the wall, the sanitary conditions extremely basic. My life back home seemed as far away as the moon. It was like going back in time. Yet she seemed at peace; content with her lot. In some ways I left her house with almost an odd pang of jealousy.

An unfortunate turn of phrase, but Chernobyl gets under your skin; the connotations of what happened there, the horrors, the tragedy. I have thought about what I saw, what I experienced, every day since. Did it happen? Did I really experience the sheer surreal of having lunch in the actual reactor canteen?

It is all a lingering spectre. Now, whenever I am in woods or see moss, I am suddenly wondering if it is safe to step on. The empty sadness of chernobyl shrouds you at times. What is left is a snap shot of a different time. Like many tragic events, it is a reminder of the human condition, both the bad side but also the good - let us not forget the heroic efforts of the firemen who sacrificed their lives and went into the reactor at the time of the disaster. Their selfless actions saving the world of a larger catastrophe.

Sometimes I feel I am drawn to derelict buildings because I often feel a little empty inside, as if I am a derelict well, or as if large pieces inside are missing. But sometimes I think derelict buildings call to me so that the silent walls and objects can somehow tell their story, reveal their secrets and histories. One day we will be nothing ourselves, one day we will become these empty shell structures and nothing will be left of us but an old shoe, left languishing in the dust. And I would want someone to spot this remnant, and capture it, to speak for me when I cannot - 'look, I was here. I lived'.

You can see my full sets of photographs documenting my time at Chernobyl in my flickr albums - Chernobyl, Pripyat, Duga Radar, Exclusion Zone house visit, the Children's Camp, and Pripyat hospital.

For a fascinating before the disaster comparison, images of life in Pripyat can be viewed on Photos of everyday life in Pripyat before the disaster.

One such location has been a fascination of mine for a long time. And that place is Chernobyl.

Photographing decaying and derelict buildings has long been an obsession of mine, something I've written and blathered on about many times. I yearn for it. I crave the ability to traipse through stale, dank crooked structures; rotten walls, peeling paint. Their ghostly existence crying out to be photographed - the documentation of manmade decline as nature engulfs it.

Photography lends itself so well to capture these haunting scenes, the emptiness, the decay - which never stops, never pauses - only within the four walls of the photograph.

Visiting Chernobyl had become a dream of mine. I had dreamed of seeing Pripyat, the city near the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, where nearly 50,000 people had lived between 1970 and 1986. On April 27th 1986, the day after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the city was evacuated, what is left is a ghost town. Buildings not used in thirty years; roads not been driven on, the swimming pool not swum in, the kindergarten cots not slept in.

This July, I was lucky enough to finally visit Chernobyl. The two day tour was probably one of the most incredible experiences of my life. I have explored many derelict buildings over the years, but apart from Imber, the small English village taken over by the military during WWII, I had never before had the chance to visit an entire ghost town - a cornucopia of abandoned treasures.

Trips to Chernobyl, have been allowed since the area has been deemed more safe, but there are still many precautions one must take when visiting (and quite rightly so). We had been given advice on what clothes to wear, and told to not touch things, or step on certain things. Moss for example, is particularly good at absorbing radiation so is likely to emit high levels of radiation so you are warned to not walk on it. You can imagine how difficult it becomes trying to avoid doing so whilst exploring Pripyat, trying to take in everything around you.

It is also strictly forbidden to remove anything from the exclusion zone. Entry into Chernobyl requires passport control, and the area is heavily guarded. You are not allowed to eat or drink whilst walking around Pripyat - and you can only do so whilst on the bus which would transport us around parts of the city which we could not travel by foot. During our stay in the Chernobyl hotel, there is a curfew by evening and no one is allowed outside after 8pm. You are screened regularly, having to stand in these bizarre 1970s sci-fi film-esque machines, that check you for any radioactive contamination.

When faced with these rules and regulations, the reality of where you are visiting very much strikes you. This is not a game, not a jolly. This is something that must be treated with respect, as you risked putting yourself in grave danger otherwise.

The trip began as we were taken to a kindergarten. The walls were seeping with branches and foliage and peeling crusty paint. What was left was a tragic reminder of the young lives who frequented there - dusty broken shoes, toys, torn books. So many items that looked like they had just been dumped. Rotting dolls like something out of a Stephen King film, and rows of skeletal wire cots that resembled an odd communal prison cell.

The personal items strewn across the decaying floorboards conjure so many questions - who wore this small shoe? Who did they grow up to be? Did they survive? Who clutched the teddy bear and dropped it that day in 1986, not realising they would never get to return to fetch it?

We were taken to many buildings and various areas in Pripyat. The culture palace, with a theatre and its stunning broken backstage.

It was a myriad of lighting rigs and grids of wires, now spookily silent, patiently waiting for the next performance that will never come.

The culture palace as it is today from the outside:

As the same culture palace as it was originally:

We saw one of the vast empty swimming pools, looking gaunt and hungry without its water; bright light streaming down onto white tiles through the huge windows - bizarrely striking against the dirt and graffiti that was building up. The suicidal looking diving platform still proudly erect, angular and defiant.

We explored a school. Pripyat had around 20 schools for the 5,000 children who lived there.

The school we visited was a zombified grange hill. So much of the ghostly remains resembled memories from my own school days: the corridors, the small chairs, books, science labs - yet these were all decomposing and decaying - vast broken rooms filled with empty dying desks, crumpled text books, written work books in perfectly scripted Russian/Ukrainian which was still legible. The poignancy was striking - when a child had worked so hard and taken so much care on this work I was stood near, little did they know it would one day be dirt ridden and lying upon a decaying floor, as part of a strange time capsule fodder for photographers.

Communist propaganda posters still hanging from the walls - Lenin, workers, anti-west diatribe. Cold war teachings. Something that seemed to only exist in history books I had seen in my own school - here they were for real.

It was in the school which I saw one of the most incredible sights I have ever witnessed - a sea of decaying gas masks. Gas masks themselves always look so alien and menacing. This surreal scene was an infinity ocean of cold war atomic nightmares. It churned your stomach, it made you gulp. The black holes for eyes, they resembled deformed leathery skulls. Gas masks, war. The threat. It was, of course, a reality for daily lives for the people of chernobyl.

One of the most impressive structures in Chernobyl that we visited was the 'woodpecker' - an incredible mammoth duga radar structure. It derived its nickname due to the sound it broadcasted - sharp, repetitive tapping noises, very much like a woodpecker.

There were many conspiracy theories over to what the radar tower's purpose was - with many insinuations and allegations of spying, and even mind control. Of course, none of these were ever proven. Now, the structure still stands proud....just eerily silent. Standing near it, you marvelled at its sheer size and formed beauty. Climbing the tower, scrambling up wobbling ladders you got the overwhelming sense of how minuscule you were. You were just an insignificant entity. The machine was the dominate power.

Inside the duga buildings, a control room contained warnings of attack, yet with oddly crude posters which almost resembled school drawings of nuclear rockets. It had a beautiful naivety, yet the science it was representing, was very much contradicting this.

One of the most famous areas of Pripyat was the fairground. It was meant to be opened on the May day celebrations - the disaster, of course, scupper these plans. The fairground that never was. The huge abandoned ferris wheel has become one of the icons of Chernobyl. Walking up to the area, the ferris wheel suddenly poked through the trees, its yellow carts so recognisable looming on the horizon. It made my skin prickle and the hairs on my arms stand up.

The fairground had languishing dogem cars, rusting away waiting to be driven; empty swing boats waiting to swing. Still. Expectant but dead. No sounds of children happily playing. Just static rusty structures waiting to die.

(For a peak at what the fairground looked like shortly before the evacuation - here is an interesting photograph of the ferris wheel)

We climbed 14 floors of stairs to the roof of a defunct crumbling residential building, and saw the incredible view across Pripyat. You could see for miles into the horizon. One side there was nothing but trees, the other side, the nuclear reactor stuck out into the landscape like a curved silver beast, glinting in the glorious sun shine. The reactor looked so close. The reactor *was* so close. You could imagine how quickly the radiation would have spread to the city....

And yet at times, as I gazed into the horizon on the gloriously sunny day, it felt so peaceful. So quiet. It was almost tranquil. Such a contrast to the thought of what had happened there.

We were taken to a shop, a factory, cafeteria, the hospital and the cinema. All places of such mundane daily routine, of pastimes, of work, or places of social interaction - now dying and deteriorating; signs hanging off, rubble strewn, windows broken, ovens caked with rust not baked goods. Vending machines. Beds. Random items abandoned - a pepsi bottle, a hard hat, pill bottles, an old vinyl record, a torn sofa. Objects of life, signs of life, yet there is no life.

The beauty of these broken items sometimes took my breath away. The huge cooling tower. The light against the beautiful broken glassed windows of the cafeteria, crystalloid patterns that could be in another life, hanging in an art gallery. The creepy children's camp - set in the forest and evocative of as many woods horror films you can imagine. The stunning and oddly satisfying athestic of peeling paint - the crusty curls clawing out of the walls as if their bony fingers were coming alive. The dark rusty signs or faded red propaganda posters; beautiful in their colour and form. The emptiness of an abandoned room, now useless in its initial purpose, dripping with this tragic well of loneliness.

It was all quite overwhelming. And sometimes macabre.

Nothing was more a deadly wake up call of the dangers in chernobyl, than the sight and sound of the Geiger counter alarm, approaching one of the most radioactive items still left in Pripyat - the claw. The Geiger counter was brought out at various times during our trip. Sometimes it was unnerving (but also sobering and important) to how suddenly you would be near an item that was setting the alarm off on the counter. Radiation - the silent and invisible assassin. There is something more frighting about a deadly threat that you cannot see, cannot smell, cannot hear.

'The claw', however, was off the scale. You are not allowed close to 'the claw' - a terrifyingly industrial metal claw that was used to clean up nuclear waste after the disaster. Our guide placed the Geiger counter near, and we watched in awe as the alarm spiralled into high pitched cacophony. This was real. This was dangerous.

We slowly crept away.

One morning of the tour, we visited the house of a chernobyl resident. An odd experience, one that I was not sure I was comfortable with. She welcomed visitors regularly, showing people around her home and land.

Money was no use to her, instead, we brought her items such as sugar and salt. She spoke to us via an interpreter, explaining that she had worked in the reactor, and had been evacuated the day after the disaster, but had returned to live a year later and had lived there ever since.

She grew many crops, and these were all tested safe for consumption. Her house was primitive, her life was basic. She lived alone with her dog and cats. Whilst she made us feel very welcome (she gave us her own homemade moonshine and bread), I felt intruding, I felt as if I was patronising her by just being there.

It was a reality check to how some people live in the world, something I am far too often blinkered to - her oven was a hole in the wall, the sanitary conditions extremely basic. My life back home seemed as far away as the moon. It was like going back in time. Yet she seemed at peace; content with her lot. In some ways I left her house with almost an odd pang of jealousy.

An unfortunate turn of phrase, but Chernobyl gets under your skin; the connotations of what happened there, the horrors, the tragedy. I have thought about what I saw, what I experienced, every day since. Did it happen? Did I really experience the sheer surreal of having lunch in the actual reactor canteen?

It is all a lingering spectre. Now, whenever I am in woods or see moss, I am suddenly wondering if it is safe to step on. The empty sadness of chernobyl shrouds you at times. What is left is a snap shot of a different time. Like many tragic events, it is a reminder of the human condition, both the bad side but also the good - let us not forget the heroic efforts of the firemen who sacrificed their lives and went into the reactor at the time of the disaster. Their selfless actions saving the world of a larger catastrophe.

Sometimes I feel I am drawn to derelict buildings because I often feel a little empty inside, as if I am a derelict well, or as if large pieces inside are missing. But sometimes I think derelict buildings call to me so that the silent walls and objects can somehow tell their story, reveal their secrets and histories. One day we will be nothing ourselves, one day we will become these empty shell structures and nothing will be left of us but an old shoe, left languishing in the dust. And I would want someone to spot this remnant, and capture it, to speak for me when I cannot - 'look, I was here. I lived'.

You can see my full sets of photographs documenting my time at Chernobyl in my flickr albums - Chernobyl, Pripyat, Duga Radar, Exclusion Zone house visit, the Children's Camp, and Pripyat hospital.

For a fascinating before the disaster comparison, images of life in Pripyat can be viewed on Photos of everyday life in Pripyat before the disaster.

Comments